Canada’s broken police force,

corrupt elite and media courtiers

Anatomy of a Cover-up: The Truth about the RCMP

and the Nova Scotia Massacres, written by Paul Palango

July 3, 2025

A trigger warning from the Mass Casualty Commission website:

The MCC offers no warnings about its credibility.

Two conclusions about this case can be drawn with certainty. The once-storied Royal Canadian Mounted Police has become a thoroughly dysfunctional mess. And the official story about the 2020 Nova Scotia mass murder is fiction.

Yes, during April 18 and 19, 2020, Gabriel Wortman went on a killing spree that ended with his life and 23 victims including an unborn child. The official story maintains that Wortman was a coercive, violent guy who abused his long-time girlfriend, became unhinged during Covid and then psychotically insane on hearing a cutting remark over social media. The RCMP, Nova Scotia’s Serious Incident Response Team and a federal/Nova Scotian commission of inquiry manufactured its version of a prelude to this horror and its sequence of events, along with a set of recommendations.

But as Paul Palango convincingly shows, the official story is wrong, dishonestly wrong. Disturbing issues remain of police competence, justice, ethics and accountability.

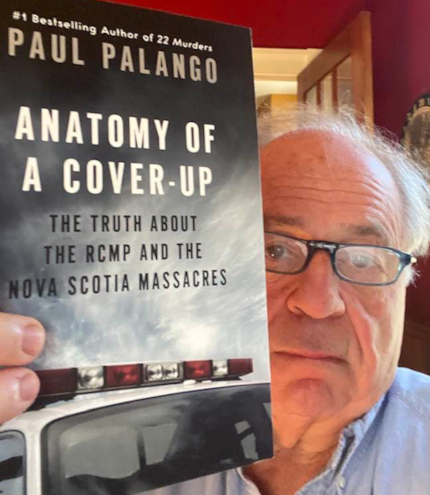

This is Palango’s fifth book examining the RCMP. The fourth, 22 Murders: Investigating the Massacres, Cover-up and Obstacles to Justice in Nova Scotia, came out in 2022 before the federal/provincial Mass Casualty Commission began its hearings. Anatomy of a Cover-up follows the MCC exercise.

Along with a band of other citizen-investigators, Palango takes an approach clashing with that of mainstream journalism. Among other non-MSM traits, he’s curious and skeptical. He looks critically at official statements, recognizes evasion and obfuscation, digs up undisclosed evidence (lots of it), reveals that evidence has been destroyed, visits important scenes and interviews people including key sources ignored by the commission. He rejects the politically correct arguments used to stage-manage a bogus inquiry.

The author with his fifth RCMP critique: Palango has

been described as Canada’s last investigative journalist.

In doing so he concludes that the Mounties’ response to Wortman’s 13-hour rampage was horrifically inadequate. That’s reflected in an abundance of ill-equipped, poorly trained officers often unsuited to police work, their terrible judgment and, emanating from the force’s top management, structural deficiencies plaguing far too many aspects of the entire nation-wide 20,000-officer force.

That itself might prompt an extensive cover-up. But as the killings continued, something else also seemed to have been hindering the cops, something they didn’t want publicly known. Palango’s scrutiny leads him to theorize that Wortman, definitely a well-known criminal, was a cop agent or informant. His Mountie handlers might have pushed him too far, eventually blowing his cover. Maybe it was fear of imminent gangland execution that drove his psychotic reaction.

That’s one hell of a lot to hide, but RCMP, SiRT, government and the commission did their best, working together “to pull off a cover-up in plain sight.” Using the last refuge of today’s most ubiquitous scoundrels, they hid behind political correctness.

The media fell for it.

Before the inquiry even began federal and provincial governments insisted, as Palango states, “that the massacres were the result of domestic violence and that any examination of what happened should be viewed through a ‘feminist lens.’” The inquiry also had to be “trauma-informed.”

With that, the MCC set out in advance to support its pre-conclusion. The “trauma-informed” mandate meant victims’ families weren’t interviewed; commission witnesses were often shielded from cross-examination; witnesses could appear by video, testify in groups or take part in a panel discussion; they could have friends, relatives or “support animals” beside them; MCC lawyers generally limited themselves to puffball questions.

The MCC commissioners: Conflict of interest, inherent bias

and flawed methodology ensured a predetermined outcome.

The MCC’s three commissioners complemented its agenda, as did their conflicts of interest. Chairperson J. Michael MacDonald had a nephew who was wounded by Wortman. As a Liberal-connected former Nova Scotia chief justice, MacDonald stayed multiple charges against former Liberal premier and federal Liberal cabinet minister Gerald Regan of sexually abusing women and girls.

Leanne Fitch was a former Fredericton police chief with cop relatives including her Mountie father, and was known for her preoccupation with identity issues. Her association with New Brunswick RCMP in the Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit must have alerted her to Wortman’s lengthy criminal career, which spanned her jurisdiction.

Kim Stanton was a LEAF legal director who wrote a book arguing that public inquiries should address “deep societal challenges.” As Palango puts it, she pushed “the post-modernist concept of a public inquiry—reason, logic, facts and the truth were tossed out the window, if need be.”

SiRT investigators were mostly retired or seconded Mounties, Palango states. The MCC’s 10 investigators and its intelligence specialist were mostly retired Toronto cops; many of them had served under former Toronto chief Bill Blair who was now federal public safety minister and “political boss” of the inquiry. MCC lawyers came from heavily ideological backgrounds.

The commission paid for lawyers to represent the murder victims’ families but, incredibly, made family members sign confidentiality agreements. The MCC constrained the participation of families’ lawyers, even blocking them from cross-examining some key witnesses.

Palango relates many examples of evidence being withheld, buried in sudden “document dumps,” manipulated or destroyed. Inside sources told him RCMP began destroying evidence soon after the murders.

Four books preceded Anatomy of a Cover-up.

Palango has begun a sixth.

Among glaring problems exposed by Palango and his allies is Lisa Banfield’s unbelievable story about the night of April 18 to the morning of April 19; Wortman’s route of departure from the Portapique area where he began killing; the RCMP’s prompt evacuation of Wortman’s criminal drinking buddy Peter Griffon and his parents but adamant refusal for nearly three hours (despite heated objection from some officers) to rescue four terrified children hiding nearby—after the mother of one pair of siblings and both parents of the other pair had been killed; RCMP wrongly declaring an injured victim dead, telling the victim’s daughter to “fuck off” and cancelling an ambulance call—without medical attention, the victim died eight hours later; the possibility that another victim was accidentally killed by a panicked cop; an incompetent pursuit that had cops setting roadblocks behind Wortman as he drove from one killing location to another unimpeded; the RCMP’s refusal to warn the public until more than 12 hours into the 13-hour horror, and then only through Twitter instead of the province’s Alert Ready system; Wortman’s stop at a Petro Canada station where a cop likely saw him before Wortman drove away to an Irving Big Stop gas station; whether Mounties followed him there, and whether they did so with the intention of killing him immediately and not necessarily for public safety.

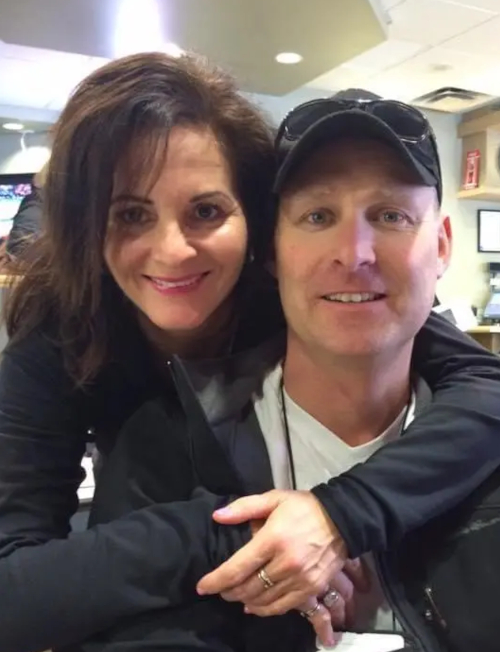

Lisa Banfield and Gabriel Wortman: Posted on Frank Atlantic

magazine, this photo likely wouldn’t clear MCC censors.

One of the MCC witnesses shielded from scrutiny was Wortman’s long-time girlfriend Lisa Banfield. Not nearly matching real evidence or witness statements, her testimony lacks any credibility. Yet the supposed nature of their relationship was central to the commission’s advance conclusion that the massacre resulted from misogyny.

In a supposed video re-enactment of the location and events of her last night with Wortman, Banfield seemed unsure of her surroundings and at times appeared to have a cop directing her. She testified before a hearing with a “sad-faced” sister on each side as she gave vague, halting, tearful information about her dubious story. Condescending MCC commissioners refused to allow cross-examination from lawyers representing victims’ families. Instead, the MCC relayed selected questions submitted in writing and cleared by the commissioners.

According to Palango, “media agreed that she was a victim of domestic violence, any other evidence didn’t matter.... She was surrounded by layers of protectors: family, friends, acquaintances, a civil lawyer, top criminal lawyers, feminists, journalists, the RCMP and the commission itself.” After her testimony Halifax reporters angrily denounced any skepticism, with one hysterical headline screaming about “The witchification of Lisa Banfield.”

They weren’t just protecting Banfield. They were protecting the RCMP, SiRT and commission investigators, who must have known about Banfield’s 19-year involvement with a guy widely known for smuggling cigarettes, alcohol, drugs, guns and grenades, for amassing an arsenal, for being suspected in arsons that preceded his real estate purchases, for driving a replica RCMP car, for threatening to kill a police officer, and for a very free-spending lifestyle that Banfield shared. Other aspects of Banfield’s relationship, too, didn’t fit the profile of an abused woman.

Wortman’s relationship with police raises questions too. Despite his 30-year criminal career being common knowledge to others, cops played ignorant. They even withheld info from a police database that would have blocked his NEXUS card, a handy convenience for this cross-border serial smuggler.

Wortman collecting $475,000: A highly irregular procedure,

except for RCMP informers and people under witness protection.

Some of the more glaring gaps between the RCMP/MCC story and evidence unearthed by Palango and his allies includes Wortman picking up $475,000 weeks before his rampage. CIBC (the bank used by the federal government and RCMP) sent the money to a Brink’s office for Wortman to collect through an extremely unusual breach of procedures. At least one source said it’s a rarely used method for RCMP to pay off informants or people under witness protection.

Large payoffs reportedly come near the end of an undercover operation. Police had recently been cracking down on biker gangs in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, the two provinces where Wortman carried out his criminal activities. Two sources told Palango that New Brunswick RCMP authorized the pickup.

Palango first reported the CIBC/Brink’s transaction in a June 2020 Maclean’s article he co-wrote with two of the magazine’s regular writers. An ex-CSIS agent named Jessica Davis then contacted Maclean’s to falsely and probably dishonestly state that the transaction was perfectly normal. As a result Maclean’s dropped Palango as a contributor, showing “how easy it can be for those in power to neutralize someone who won’t play their game.” Cops and the MCC continued to deny that Wortman was a police agent or informer—although the MCC carefully specified “in Nova Scotia.”

Another official account that falls apart under scrutiny is Wortman’s supposed driving route in and then away from the Portapique area where the first 13 killings took place. The cop/MCC version might be intended to pin resident Corrie Ellison’s death on Wortman. Palango says it’s plausible that he was shot by a panicked Mountie.

RCMP union boss Brian Sauvé: His hero myth benefited management more

than rank-and-file officers. As one ex-Mountie said, constable Heidi Stevenson

“died because she was a victim of the RCMP’s incompetence. You’d think

the union would have raised issues.”

One of the most sensationalized events of the official story was the “shootout” between Wortman and RCMP constable Heidi Stevenson. The cop/MCC/cop union line claimed that Stevenson seriously wounded Wortman before he shot her dead. Officialdom supports the story mainly through a highly dubious forensics report, flat-out denial of several witness statements and over-the-top union and media hype.

Most likely Stevenson didn’t fire a single shot.

Yet as unofficial evidence came to light, National Police Federation president Brian Sauvé pumped his dishonest shilling. Media upheld the union boss’ shit credibility. The MCC “twisted itself into knots to endorse the RCMP’s version of events.”

Apart from the need to concoct a gratifying hero myth, the official story might be intended to cover up blatant examples of RCMP incompetence—all too typical examples.

Stevenson wasn’t qualified to use a carbine, the RCMP’s only standard-issue weapon appropriate to deal with Wortman’s firepower. Some RCMP trainees reportedly flunk the carbine test deliberately to ensure safe desk jobs. Stevenson flunked easily. She got caught four times failing to utilize the gun’s safety. She then managed to get through her 23-year career doing very little real police work. Still a constable, and with no appropriate experience, her seniority put her in charge of the last part of Wortman’s pursuit.

Her death speaks volumes about a disastrously incompetent series of RCMP decisions, many (not all) Mounties displaying hapless ineptitude and an overall dysfunctional police force.

Cops finally got Wortman at the Irving Big Stop. But even with the madman dead, questions remain: Did the Mounties set out in advance to kill him immediately? And, if so, did they have a motivation other than public safety?

The manner of Wortman’s death comprised another MCC snowjob. One aspect of the RCMP evidence turned out to be another faulty forensics report. An examining doctor refuted other fictional elements.

An MCC lawyer resorted to manipulating surveillance video. She refused to play the videos at the hearing, instead confusing attendees by showing individual frames, with time stamps removed, entirely out of sequence while mixing frames from one camera angle to another.

One of Palango’s collaborators, Frank Atlantic editor Andrew Douglas, launched a submission to have the MCC release the entire surveillance videos. Showing uncharacteristic mainstream interest, CBC, CTV, Canadian Press and Global joined in. When the MCC finally complied, Palango and Douglas noticed sections were missing. Nevertheless they were able to piece together the hidden story.

The two cops didn’t, as the official story maintained, just stop for gas, happen to notice Wortman, approach him and, after thinking they saw him holding a gun, start shooting. Their actions show they knew where he was in advance and arrived with the intention of killing him immediately. Another RCMP/MCC big lie had proven false.

For all that, CBC, CTV, CP and Global backed off of the story, refusing to point out that the videos discredited the official lie.

But, apart from all the other lies, why did the RCMP/MCC push this one? Wortman alive would hinder a cover-up that he was working covertly for Mounties, which could explain police tolerance of his lengthy, conspicuous criminal career. That likelihood, and its attendant possibility that Mounties blundered the undercover operation, becomes all the more plausible due to so many obvious RCMP/MCC falsehoods.

Three years of official investigation and inquiry only hid the circumstances behind 23 innocent deaths. Thanks to Palango and his allies, some of the real story has come to light. As for the remaining uncertainty, they’ve raised questions that challenge Canada’s political, legal and police establishment, as well as Canada’s media.

Related:

A B.C. perspective on Paul Palango’s RCMP exposé

Go to News and Comment page